Would you be totally fine if your boyfriend’s favorite hobby was to put on women’s clothes and make-up? Barbara, a heterosexual crossdresser from Illinois wrote, “Before long I realized that [my wife’s] image of me as a husband had been shattered, and she was no longer able to accept me in that role, even sexually” (Transvestia 1968). Some crossdressers reported that their feminine clothes were taken and burned in the incinerator after their wives found out their “deviant” behavior. In many cases, the discovery led to divorce. Why is there such a visceral reaction to someone putting on some clothes?

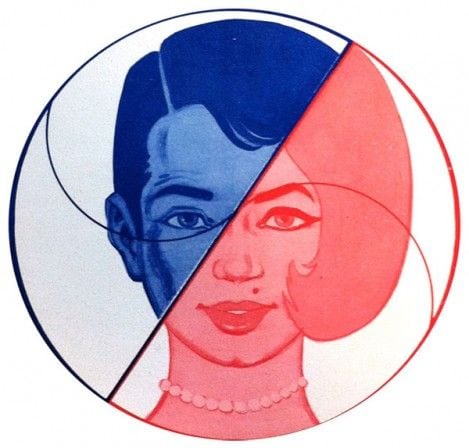

Crossdressing was long considered an activity practiced exclusively by gay males, but in the 1950s, heterosexual males who like to crossdress began to have private meetings (Biegel 108-22). According to the Journal of Social History (2011), after experiencing the destructiveness of World War Two, people wanted three things: “to be happy, to be affluent, and to be secure” (729). In the face of this, gender nonconformity stood as a threat to the home and nation while prescriptive gender norms structured how men and women “understood themselves as gendered and sexual beings”—as masculine men, feminine women, strong breadwinning husbands and dutiful homemaking wives” (JSH 731).

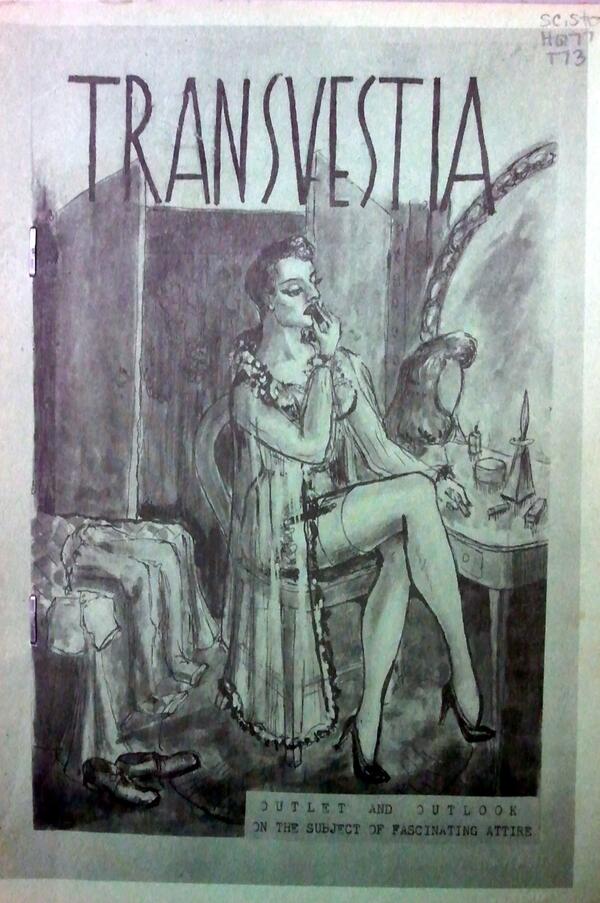

This binary gender system was bolstered during the postwar era. It was a powerful force in the domestic and intimate lives of many Americans in the 1960s, 1970s, and even now. It made gender nonconformity an often scary and sometimes isolating way of being. Crossdresser Joy Lynne from Colorado declared, “Transvestism has been a long, lonesome road to walk, wrought with self-doubt, secrecy, frustration, tension, and the lack of understanding. The polarized emotional experience of dressing ranged from sheer ecstasy and pleasure to deep, guilt-ridden feelings.” Meanwhile Joy’s wife felt that he was losing his masculinity when she first discovered his secret. However, after she read several issues of Transvestia, a magazine about transvestism, she became more accepting of her husband’s behavior. Because of her acceptance of his full expression of himself, they were “happier than ever” after that (Transvestia 1972).

Supportive wives often function as knowledgeable advisors, “offering make-up advice, fashion tips, and instructions on how to behave femininely” (JSH 734). In return, their cross-dressing husbands become the “help-mates” of their wives (JSH 734). Crossdresser Joanna from Washington states that “one of the things that [my wife] really likes is when I put my apron on…and proceed to do the housework” (Transvestia 1961). From here, we can understand that transvestism/heterosexual crossdressing could foster a happy marriage. Moreover, it is suggested that heterosexual crossdressers are more likely to be sensitive, understanding, and caring than those who do not practice it. The wife of crossdresser Carrol exemplifies this in her claim that, “it is the fact that he feels things very deeply and I think, is more understanding of me, being a girl himself at times” (Transvestia 1964).

In conclusion, transvestism/heterosexual crossdressing should not be regarded as a wrong, taboo, or abnormal behavior. It can promote deeper compatibility and understanding between marriage partners. More importantly, we should always keep in mind that gender norms are a social product—that we, human beings, are supposed to be the ones who construct the norm rather than having it construct (or constrict) us.

References:

Barbara, “The Way It Was.” Transvestia #54, December 1968.

Hill, Robert. “We Share a Sacred Secret”: Gender, Domesticity, and Containment in Transvestia’s Histories and Letters from Crossdressers and Their Wives.” Journal of Social History, Xavier University, 2011.

Letter from Joanna, Transvestia #7, January 1961.

Lynne, Joy. “You’ve Come a Long Way Baby.” Transvestia #75, 1972.

Wife’s note follows Carol’s history, Transvestia #29, October 1964.