How many times have you heard of the word “intersex”? How many intersex people have you met in your life? Perhaps you can count with only one hand. However, the fact is, in 1 out of 100 births there is a baby whose body differs from standard male or female (“How Common”). According to the Intersex Society of North America (ISNA), “Intersex is a general term used for a variety of conditions in which a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male” (“What Is,” par. 1).

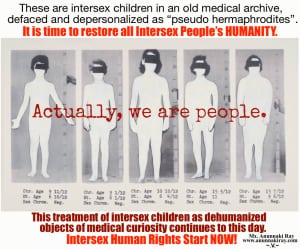

Before the word intersex was invented, “hermaphrodite” or “hermaphroditism”—which conjures images of “freak of nature, hybrid, impostor, sexual pervert and unfortunate creature”—was the word used in the early medical literature and language (Ries 536). In the early 1990s biologist Richard Goldschmidt started to call the discordance between the multiple components of sex anatomy “intersex”. Now “intersex” and “hermaphroditism” are broadly being called disorders of sex development (DSDs) in medical settings. Due to those negative connotations of the word intersex, intersex people and their parents often feel humiliated and embarrassed by their so-called “disorder.”

Calling intersex a “disorder” implies that something is medically wrong and needs to be corrected. But the fact is that “unusual sex anatomy does not inevitably require surgical or hormonal correction” (Reis 538). In fact, the so-called normalizing genital surgeries that are undertaken during infancy barely normalizes the anatomy but still causes side effects such as “pain during sex”, “less-than-fully-functional sex organs” and “recurrent infections” (Brue 106).

Drawing on Suzanne Kessler’s suggestion that “gender ambiguity is ‘corrected’, not because it is threatening to the infant’s life, but because it is threatening to the infant’s culture” (32), using the word disorder embodies a crucial point that most of the surgeries have primarily social rather than medical goals (Ries 539). As we know, in order to simplify social interactions and maintain order, sex categories get simplified into male and female. The ways in which intersex bodies have been pathologized are based on “social anxieties about marriage, heterosexuality and the insistence on normative bodies” (qtd. in Reis 2005).

From the perspective of feminism, we should think of sex, like gender, on a continuum, as something more flexible than strictly female or male. Calling intersex a disorder of sex development is entrenched in “a denial of a core feminist and intersex-activist principle regarding the fluidity of sex and gender” (Ries 539).

Instead of labeling intersex people as having a “disorder,” understanding the notions of the relationships between biological sex, sexuality, desire, and culturally influenced gender roles are what we should focus on. In fact, intersex anatomy doesn’t always show up at birth. Sometimes one isn’t found to have intersex anatomy until one dies of old age and is autopsied. That is to say, no one has the right to call intersex people as disorder since he/she might be also intersex. Someone’s sex is their own business, not yours. Just because a sexual reproductive make-up falls outside the norm, does not mean there is anything unnatural or wrong about it — we should embrace the entire messy spectrum of sex and gender.

References:

“How common is Intersex?” Intersex Society of North America. 2008. Web. 9 June 2016.

Kessler, S. J. Lessons from the Intersexed. New Brunswick: Rutgers Univ. Press, 1998.

Ries, Elizabeth. “Divergence or Disorder? The Politics of Naming Intersex.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. Vol. 50. No. 4. John Hopkins Univ. Press, 2007.

“What is Intersex?” Intersex Society of North America. 2008. Web. 9 June 2016.